The Bullwhip Effect (Part I)

Monday, January 17, 2011 at 11:16PM

Monday, January 17, 2011 at 11:16PM There were interesting comments made last fall at the second annual meeting of the Arkansas Association of Food Protection. The comments made by Frank Yiannas, Walmart's Vice-President of Food Safety, continue to resonate with me.

The first thing that struck me was Yiannas' belief that the U.S. is currently experiencing several food safety incidents per year on the scale of the Jack in the Box incident of the early 1990's. That's a chilling perception. In the e. coli epidemic of 1993, four children died and hundreds of others became sick in the Seattle area as well as California, Idaho and Nevada, after eating undercooked and contaminated meat from Jack in the Box. It was the largest and deadliest e. coli outbreak in American history up to that time.

Another takeaway was Yiannas' belief that the food industry is consequently experiencing a "global trust bust" when it comes to food safety.

I've been thinking a lot about Yiannas' comments and here are some of my conclusions ....

A significant reason for the continuing series of food safety crises (notwithstanding the recent passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act in the United States) is that the food industry's global and domestic supply chains are increasingly experiencing the Bullwhip Effect. This effect is directly attributable to the inefficiencies of one-up/one down supply chain information sharing.

What do I mean by one-up/one down information sharing? The requirement of one-up/one-down means that vendors must know what is going on inside of their four walls which means they must know what is coming in and what is going out. Representative laws or regulations requiring one-up/one-down information sharing are:

- EU General Food Law

- Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) plans

- US Bioterrorism Act of 2002

- US Food Safety Modernization Act

Industry will tell you that one-up/one down information sharing is the way it's "always been done" in supply chains. It ignores, avoids or by-passes many or most of the efficiencies of computer networking and the Internet. It also avoids or by-passes many the thorny "data ownership" and privacy issues presented by the Internet.

But the "global trust bust" in food safety is building a fire under the boiler, so to speak. And the boiler is reaching its boiling point. It's looking less and less like things can be done the way they've "always been done".

Food safety officials in a recall investigation are like consumers, albeit armed with law enforcement powers. The character above who is wielding the bullwhip could just as well be a consumer as a recall authority. The bullwhip, whether wielded by a consumer or a food saftey recall authority, is representative of a the effect of a demand.

When the Bullwhip Effect appears it is clear evidence of a less than optimal supply chain directly attributable to the inefficiencies of one-up/one-down information sharing. When a consumer makes a demand for a product, the Bullwhip Effect causes product restocking to take days, weeks, or longer ...

... similarly to how it takes days, weeks, or longer for a demand in a traceback investigation to provide the information required for determining (hopefully) the roots of the contamination and how pervasively contaminated a supply chain has become. A consumer who comes to a store to purchase a product that is out of stock causes a Bullwhip Effect in the supply chain. Similarly a food safety recall authority who comes to the store to find out why a customer became sick (or died) also causes a Bullwhip Effect in the supply chain.

OK, so you say, "What can be done about it?"

Well, the food safety recall authorities know what they want:

[T]he regulators want a traceability system that is consistent, speedy, covers the entire supply chain, has electronic records, has interoperable systems, and covers domestic and imported foods. ”

In other words, they want it all! The label they have given to what they want is a "whole chain" traceability system. A "whole chain" product tracing system consists of information elements provided by persons in the supply chain to other persons in the supply chain or to regulatory officials (e.g., during a traceback investigation). See Product Tracing Systems for Food, 74 FR 56843 (3 Nov 2009). To the right is a simple drawing of the real-time, "whole chain" monitoring that government regulators seek in order to overcome the Bullwhip Effect in food recalls.

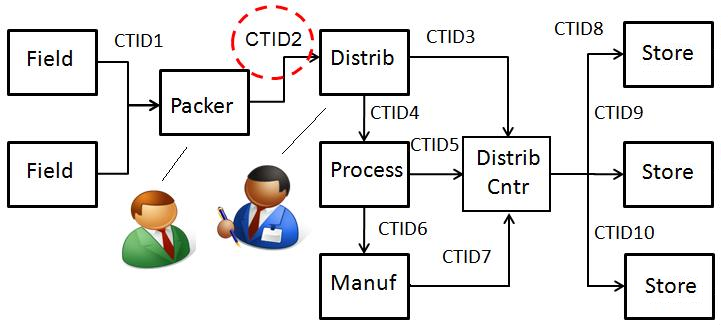

To drill down a bit more, the government seeks to conduct real-time monitoring of the critical transactional events (CTEs) of supply chains.

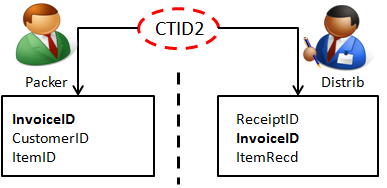

And they want to see electronic one-up/one down transactional information sharing like this ...

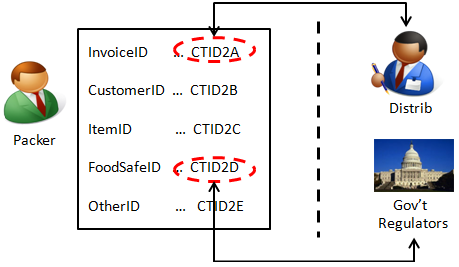

... to become something more like this ....

The challenge for industry is that government wants "whole chain" traceability and, "[o]n top of that, [they want] industry to develop the tools and to pay for the system."

But that's a real challenge for industry if for no other reason than that the government regulators have left one critical player out of the CTE supply chain, that being ...

... the customer.

But then, come to think of it, industry has also essentially left the customer out of the equation.

Continued in Part II.