The Bullwhip Effect (Part III)

Saturday, January 22, 2011 at 1:01PM

Saturday, January 22, 2011 at 1:01PM

Return to Part II.

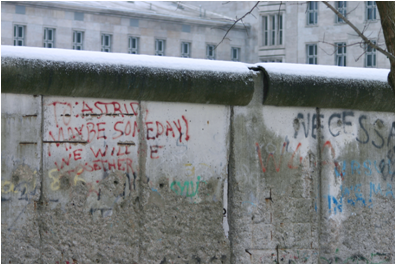

The writing is on the wall. The writing is on the Facebook Wall, like it was on the Berlin Wall. Only this time the writing is in real-time. The is in the real-time that it takes to save a life or protect an innocent company from bankruptcy by suspicion. From bankruptcy by the Bullwhip Effect.

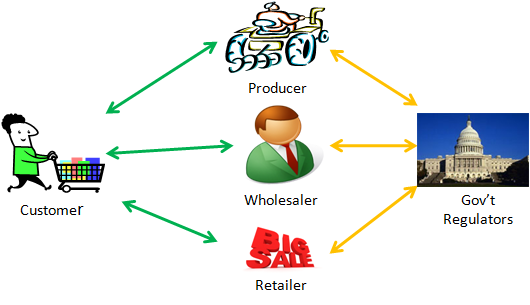

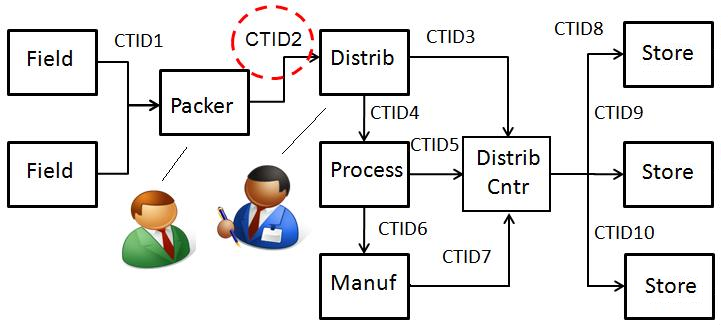

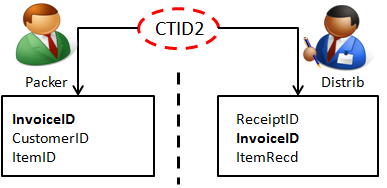

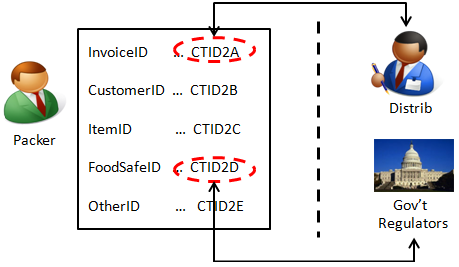

Ironically, it won't be the really bad guys who are caught in real-time. You know, the ones who commit out and out fraud. Instead, It will be the companies who really are trying to play by the rules. Who are doing their best to keep the trust of their suppliers and their customers. But even those good companies who are caught up in a recall will benefit from the elimination or reduction of deaths, sicknesses and legal liabilities that would otherwise occur under the good 'ol one-up/one-down paradigm. Instead of hundreds or thousands of people becoming sick from a pepper salmonella contamination over a period of months, flattening out the Bullwhip Effect will mean that significantly fewer people will be sickened before the government regulators react with real-time information at their finger-tips.

As an attorney who has had a fair amount of jury trial experience, I find myself wondering what a jury of Facebook users would think about questions like these in determining a food company's liability?

- Could the company have responded in real-time to the food safety incident?

- Did the company take full advantage of real-time technologies for providing food security for its customers?

- Was the company a good corporate citizen or did it recklessly ignore real-time technologies to the detriment of its consumers’ health?

Actually, it's not inconceivable that a jury comprised entirely of users of social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) would be seated even today. I wonder how much ag and food companies have thought about that? It may even now be almost impossible for their attorneys to avoid juries who in their daily lives are reading the real-time writing on the Facebook Wall. But the companies who early adopt and bring forth VRM and whole chain traceability will be the companies who will benefit even if they end up in court. At least they will be able to look the jury in the eye and say, "We acted as good corporate citizens with the best available real-time technology. We saved lives that might otherwise have been lost. We played by the rules and we didn't try to bend them."

But the fraud-committing bad guys, they'll surely run the greater risk of being bankrupted into oblivion.

Juries rest at the foundation of democracy here in the U.S. They give voice to the voiceless. They send messages (i.e., verdicts and liability judgments) out to our society that are often heard as clearly as if the President had signed significant Congressional legislation. They're not real-time messages but sometimes they kind of feel like it because they often seem to come out of nowhere.

A few years ago I prosecuted a prisoner for escaping from a penitentiary. He wasn't a bad guy in a violent sense. In fact, he wasn't violent at all. He was a middle-aged, property thief who was a kind of 'nice guy' among bad guys. The prison warden even designated him as a trustee so that he could work on the farm outside of the walls of the Big House. At least until he tried to escape at all of about 15 mph (24 kph) on a farm tractor. It didn't take long to catch him.

A few years ago I prosecuted a prisoner for escaping from a penitentiary. He wasn't a bad guy in a violent sense. In fact, he wasn't violent at all. He was a middle-aged, property thief who was a kind of 'nice guy' among bad guys. The prison warden even designated him as a trustee so that he could work on the farm outside of the walls of the Big House. At least until he tried to escape at all of about 15 mph (24 kph) on a farm tractor. It didn't take long to catch him.

The prosecution of escape cases rarely go to trial because, well, what's the point? I offered the prisoner's attorney the minimum sentence of 2 additional years to do just so we wouldn't have to pick a jury but he said that his client wanted a trial. What? Huh? Why? "He wants a trial and I don't know why," the attorney said with a shrug. He was as perplexed as I was. Both of us knew that the prisoner risked receiving the maximum of 7 additional years in prison for making the judge and members of the jury go through an unnecessary procedure. That is, for wasting everybody's times.

So one afternoon the prisoner was transported over from the Big House to the courthouse. We picked a jury. I rested my case. The prisoner took the witness stand. He swore to tell the truth. His attorney asked him to tell his story. The prisoner said, "I escaped".

There is a tenet among trial lawyers that you should never ask a question that you don't know the answer to. I didn't have to ask the prisoner a question at all. He was going to be convicted. He knew he was going to be convicted. The jury's decision was made for them. There was no need for deliberation. The jury members were relieved that they would all be home well before dinner. But I had to ask him because I genuinely wanted know, "Why have we gone through this process of picking a jury and conducting a trial when you admit straight up to escaping?"

"I've been in and out of prison my whole life," the prisoner said. "The 5 or 6 times that I've been put back in prison was because whomever my attorney was at the time told me to plead guilty. I always did what I was told. This time, I wanted to do it my way. I wanted my day in court. I wanted to be heard. I escaped ... but now I have had my day in court. That's all I wanted."

The jury was touched. There was even a knowing smile or two in the jury box. They quickly came back with a verdict - the 2 year minimum that I had offered to begin with. The prisoner went back home to his cell in the Big House that night with a smile on his face. He had had his day in court. A jury of his peers had actually listened to him. And heard him.

I was touched, too. It was one of those teachable moments that we find ourselves surprisingly carrying with us, and from time to time reflecting upon. People want to be heard. People don't want to be managed into "doing the right thing" and muzzled in the process. Even in a losing effort. The need to be heard is a powerful human need. That's the bull's-eye that VRM is aiming to hit. It's the right target.

I was touched, too. It was one of those teachable moments that we find ourselves surprisingly carrying with us, and from time to time reflecting upon. People want to be heard. People don't want to be managed into "doing the right thing" and muzzled in the process. Even in a losing effort. The need to be heard is a powerful human need. That's the bull's-eye that VRM is aiming to hit. It's the right target.

I began this three part series of journal entries referencing comments that Frank Yiannas made at the second annual meeting of the Arkansas Association of Food Protection. He said something else that I hadn't mentioned. He said that when he first took on the food safety position at Walmart that their marketing department wanted to broadcast the message that food safety was now a priority at Walmart. Yiannas said that - to the surprise of the marketing folks - he nipped that at the bud. His reason? Food safety is not a priority because ... priorities change. Food safety is a commitment ... and commitments don't change.

If we can just get VRM and whole chain traceability connected with Yiannas' corporate philosophy of food safety committment, there will be a whole lot more customers feeling like they are able to do it their way with companies who are truly acting as good corporate citizens in a real-time world. Lives will be saved. Customer loyalty will be increased. Liability risks for companies and industries will be eliminated or reduced. Lots of money will be made.* And maybe, just maybe, the global trust bust - identified as being real by the largest retailer in the world - will begin to fade away.

This is the third and final part of a three part journal entry. Feel a need to comment? Please do so at Data Ownership in the Cloud on LinkedIn.

________________________________

* And kept from the hands of the dreaded trial lawyers! :-) Like Bill Marler says, "Put me out of business - please!"